One day, I was researching some of my relatives who come from Kamenets-Podilsky (Bessarabia) map on an earlier post here. It’s in western Ukraine these days. Leaving aside the usual misspellings caused by different methods of transliterations, I found more than one family member was recorded as from Kamenets-Podilski, Khabarovsk, Russia. At first I assumed, it was just a mistake. But then I found some more, so I though I had better look into it. Google maps could indeed find a Kamenets-Podilski near Khabarovsk. It’s quite common to name new towns after the place you migrated from: there are plenty of examples in the US, after all. So I assumed that these people had migrated from the Ukrainian place. But why to go to Siberia? Why go East not West?

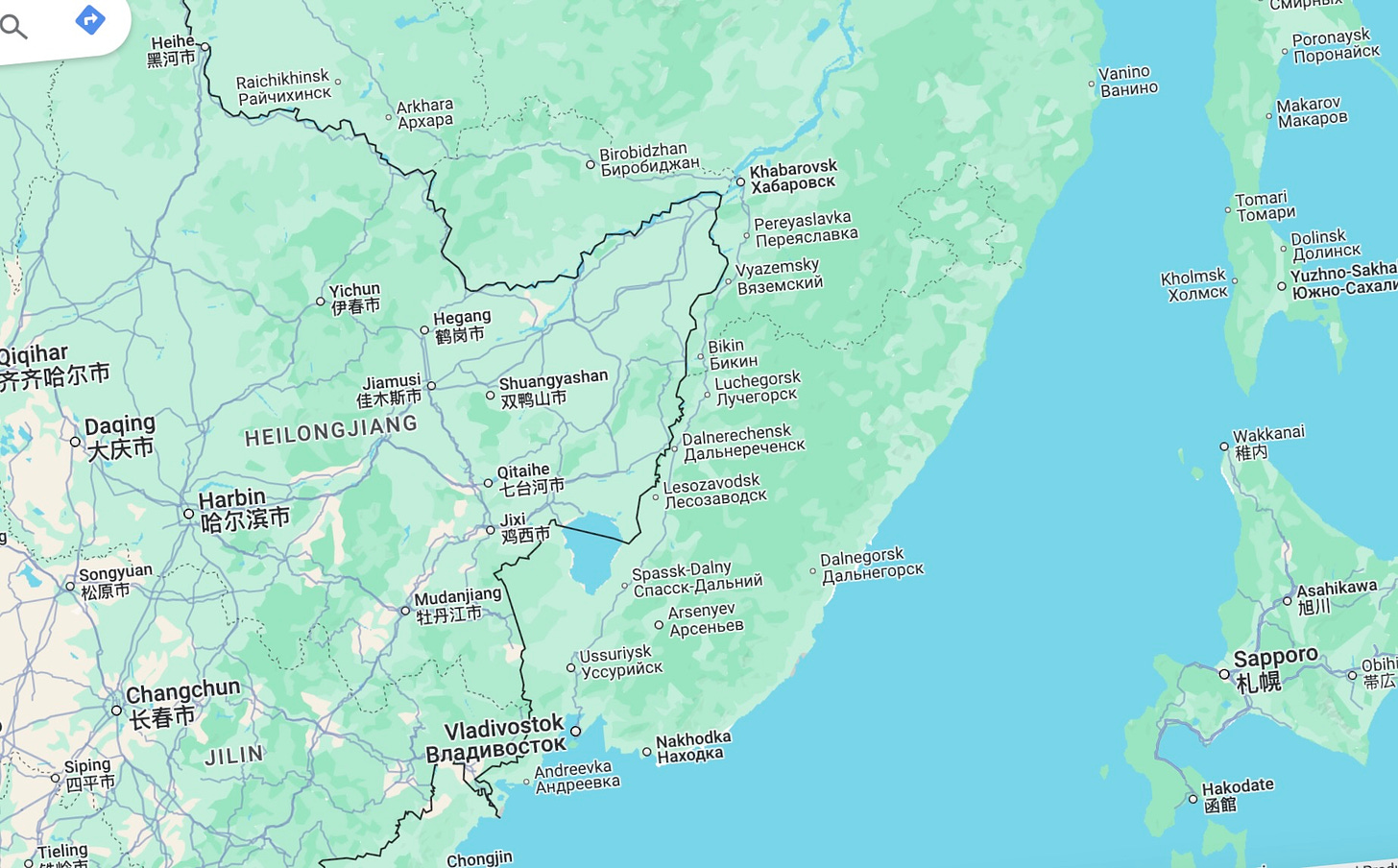

Since I have actually been to Khabarovsk on a trip on the Trans-Siberian railway in 1975, I know where it is, not far from the Pacific coast of Russia, close to the Chinese border and across the water from Japan.

I remember it as a rather pleasant town with rather neoclassical buildings and traditional wooden houses. It’s also the Russian town appearing in Kurosawa’s award winning film Dersu Uzala. The Guardian says:

This humanist masterwork is close in spirit to John Ford and has many of the ingredients of a classic western. The central relationship recalls that between the pioneers and the native Americans in the novels of James Fenimore Cooper, though the violent incidents happen offstage.

You can watch the film on Youtube. But just as for the rest of US settler-colonialism, this romantic portrayal of the relationship between pioneers and native Americans was not always accurate, and leaves out the devastation occurring to the every day life of the native people in Eastern Siberia. For a lively read, try Rane Willerslev’s 2012 account of how fur trappers live now: On the run in Siberia.

Later I remembered about Birobidzhan, the Jewish Autonomous Region located on the Trans-Siberian Railway, near the China–Russia border set up during the 1930s. I never thought to go there on my trip, and I doubt if I would have got permission. But it seems it is quite close to Khabarovsk. I expected that Kamenets-Podolski would be in Birobidzhan, but it is a little further to the south-west of Khabarovsk.

According to Wikipedia, Jewish communists believed that the Soviet Union's creation of Birobidzhan was the "only true and sensible solution to the national question." The Soviet government used the slogan "To the Jewish Homeland!" to encourage Jewish workers to move to Birobidzhan. The slogan proved successful in convincing Soviet Jews as well as Jews from other countries. Jews who moved there had hoped to create a place of safety where Jewish culture and the Yiddish language could thrive.

In 1935, Ambijan received permission from the Soviet government to aid Jewish families traveling to Birobidzhan from Poland, Romania, Lithuania and Germany. Jewish workers and engineers traveled to Birobidzhan from Argentina and the United States as well. This campaign by the Soviet government was known as the Birobidzhan Experiment.

There’s an interview here with Masha Gessen, whose book “Where the Jews aren’t: the Sad and Absurd Story of Biribidzhan, the Jewish Autonomous Region”, explains why the experiment failed: basically nothing was prepared for would-be colonists. By 1936, Jews in Birobidzhan were negatively targeted, and targeted in this very Soviet way specifically for what they came there for - for nationalism, for promoting the Yiddish language, for what they were told was a good thing just a couple of years earlier.

So it seems unlikely but not impossible that this Jewish family were drawn to move to Birobidzhan.

However, as professional genealogists constantly stress, you need to collect all the information you have already and form a proper research question to check. Which I always resist, even in my paid work with research on a completely different topic. I like to stew in the material to see what pops out, to expand the box outside what seem to be the boundaries, and generally irritate the hell out of colleagues by looking at lots of irrelevant things until it’s time to settle down and a deadline is appropriate. But no deadlines in my family history so finding time for more material is never a problem!

Eventually, I decided to check exactly which people I had found on Ancestry who had this place in their background. I found seven trees with the same three generation family, with the Kamenets-Podolski (Khabarovsk) location. The family members are consistent. The grandfather dies there (but there is no information how he got there or when he died) and his wife has very little information. Unfortunately she seems to be a crucial link in my tree! From him, there is one daughter who marries a man also born there in the 1880s (according to the tree) and they have five children born there. Another sister also seems to be born there, (but not other siblings).

The 1920 US census showed the time they arrived in New York: in 1907 for the father and 1911 for the mother and the rest of the brood. Photos of the couple and children are identical on each of the trees where photos exist.

Clearly the time is wrong for the family going to Birobidzhan. Since the parents were born and met in Siberia, their families must have already been there in the 1880s. So many questions remain.

So what were Jews doing so far beyond the Pale of Settlement? And why, when the grandfather could have earlier gone straight to America from the Kamenets-Podolski in Ukraine, did he decide to go East?

How did the Jewish grandfather end up in that Kamenets-Podolski, so far away from the other one, which had a large Jewish population? It’s not a place you go to die, unless it has a prison camp.

How did a Yiddish speaking mother and 5 kids manage the journey from Khabarovsk back to Europe let alone to the US. How long did it take her, and how did she travel? The Trans-Siberian Railway was built between 1891 and 1916, so they could hardly have used that for much of the journey.

So I have written to the owner of the family tree with most information to see what else they know about this family. Watch this space! But not holding out too much hope since we all know messages are often not answered.

Oh, that's fascinating, Helene! I didn't know anything about this Birobidzhan experiment. We have a wonderful community of Russians here in San Francisco, exiles, as I understand it from the east following the Bolshevik Revolution.